Read ebook «The Cyberiad» online

Font size:

“Not that I have anything against you personally, you understand. But you know too much, old boy. So I really think it’s best we put you in the clink. Yes, into the clink with you!” And he gave a nasty laugh. “That way, when I leave the force, no one—not even you—will have the foggiest notion where, or rather who, I am! Ha-ha!”

“But Your Majesty!” Klapaucius protested. “You don’t know all the dangers of the device. Suppose you entered the body of someone with a fatal illness, or a hunted criminal…”

“No problem,” said the King. “All I have to do is remember one thing: after every switch, grab the horns!”

And he pointed to the broken desk, where the device lay in an open drawer.

“As long as, each time,” he said, “I pull it off the head of the person I just was and hold on to it, nothing can harm me!”

Klapaucius did his best to persuade the King to abandon the idea of future personality transfers, but it was quite hopeless; the King only laughed and made jokes, then finally said, clearly enjoying himself:

“I won’t go back to the palace—you can forget about that! Anyway, I’ll tell you: I see before me a great voyage, traveling among my loyal subjects from body to body, which, after all, is very much in keeping with my democratic principles. And then for dessert, so to speak, the body of some fair maiden—that ought to be a most edifying experience, don’t you think? Ha-ha!”

And he threw open the door with a great, hairy paw and bawled for his subordinates. Klapaucius, seeing they would lock him up for sure unless he acted at once, grabbed an inkwell and tossed its contents into the King’s face, then in the general confusion leaped out a window into the street. By a great stroke of luck, there were no witnesses about, and he was able to make it to a populous square and lose himself in the crowd before the police began pouring from the station, straightening their shakos and waving their weapons in the air.

Plunged in thoughts that were far from pleasant, Klapaucius walked away from the harbor. “It would be best, really,” he said to himself, “to leave that incorrigible Balerion to his fate, go to the hospital where Trurl’s body is staying, occupied by the honest sailor, and bring it to the palace, so my friend can be himself again, body and soul. Though it’s true that that would make the sailor King instead of Balerion—and serve that rascal right!” Not a bad plan perhaps, but inoperable for the lack of a small but indispensable item, namely the transformer with the horns, which at present lay in the drawer of a policeman’s desk. For a moment Klapaucius considered the possibility of constructing another such device—no, there was neither the time nor the means. “But here’s an idea,” he thought. “I’ll go to Trurl, who’s the King and by now has surely come to his senses, and I’ll tell him to have the army surround the harbor police station. That way, we’ll recover the device and Trurl can get back to his old self!”

However, Klapaucius wasn’t admitted to the palace. The King, so the sentries told him, had been put under heavy electrostatic sedation by his physicians and should sleep like a top for the next twenty-eight hours at least.

“That’s all we need!” groaned Klapaucius, and hastened to the hospital where Trurl’s body was staying, for he feared that it might have already been discharged and irretrievably lost in the labyrinth of the big city. At the hospital he presented himself as a relative of the one with the broken leg; the name he managed to read off the in-patient register. He learned that the injury wasn’t serious, a bad sprain and not a fracture, though the patient would have to remain in traction for several days. Klapaucius, of course, had no intention of visiting the patient—it would only come out that they weren’t even acquainted. Reassured at least that Trurl’s body wouldn’t run off on him unexpectedly, he left the hospital and took to wandering the streets, deep in thought. Somehow he found himself back in the vicinity of the harbor and noticed the place was swarming with police; they were stopping everyone, carefully comparing face after face with a description each officer carried with him in a notebook. Klapaucius immediately guessed that this was the doing of Balerion, who at all costs wanted him under lock and key. Just then a patrol approached—and two guards rounded the corner in the opposite direction, cutting off his retreat. Klapaucius quietly gave himself up, demanding only that they take him before the Commissioner, saying that it was most urgent, that he was in possession of extremely important evidence concerning a certain horrible crime. They took him into custody and handcuffed him to a burly policeman; at the station, the Commissioner—Balerion— greeted him with a grunt of satisfaction and an evil twinkle in his beady eyes. But Klapaucius was already exclaiming, in a voice not his own:

“Great One! High-high Police Sir! They take me, they say me Klapaucius, me not Klapaucius, not-not, me not even know who-what Klapaucius! Maybe that Klapaucius he bad one, one who bam-bam horns in head, make big magic, bad magic, make that me not me, put head in other head, take old head, horns, run zip-zip, O Much Police Sir! Help!”

And with these words did the wily Klapaucius fall to his knees, shaking his head and muttering in a strange tongue. Balerion, standing behind the desk in a uniform with wide epaulets, blinked as he listened, somewhat taken aback; he gave the kneeling Klapaucius a closer look and began to nod, apparently convinced—-unaware that the constructor, on the way to the station, had pressed his own forehead with his free hand, to produce two marks not unlike those left by the horns of a personality transformer. Balerion had his men release Klapaucius and leave the room; when the two of them were alone, he asked him to relate exactly what had happened, omitting nothing. Klapaucius replied with a long story of how he, a wealthy foreigner, had arrived only that day at the harbor, his ship laden with two hundred cases of the prettiest puzzles in creation as well as thirty self-winding fair maidens, for he had hoped to present these to the great King Balerion; how they were a gift from the great Emperor Proboscideon, who in this way sought to express his boundless admiration for the great House of Cymberia; but how, having arrived and disembarked, he had thought to stretch his legs a little after the long journey and was strolling peacefully along the quay, when this person, who looked just like this (here Klapaucius pointed to himself) and who had already aroused his suspicions by gazing upon the splendor of his foreign dress with such evident rapacity—when this person, in short, suddenly ran towards him like a maniac, ran as if to run him down, but doffed his cap instead and butted him viciously with a pair of horns, whereupon an extraordinary exchange of minds took place.

Klapaucius put everything he had into the tale, trying to make it as believable as possible. He spoke at great length of his lost body, while heaping insults upon the one it was now his misfortune to possess, and he even began to slap his own face and spit on his own legs and chest; he spoke of the treasures he’d brought with him, describing them in every detail, particularly the self-winding maidens; he reminisced about the family he’d left behind, his ion-scions, his hi-fi fido, his wife, one of three hundred, who made a mulled electrolyte as fine as any that ever graced the table of the Emperor Himself; he even let the Commissioner in on his biggest secret, to wit, that he had arranged with the captain of his ship to hand the treasures over to whomsoever came on board and gave the password.

Balerion listened greedily, for it seemed quite logical to him that Klapaucius, seeking to hide from the police, should do so by entering the body of a foreigner, a foreigner moreover attired in splendid robes, hence obviously wealthy, which would provide him with considerable means once the transfer were effected. It was plain that a similar scheme had hatched in the brain of Balerion. Slyly, he tried to coax the secret password from the false foreigner, who didn’t require much coaxing, soon whispering the word into his ear: “Niterc.” By now the constructor was sure Balerion had taken the bait: the King, loving puzzles as he did, couldn’t bear to see them go to the King, since the King, after all, was no longer he; and, believing everything, he believed that Klapaucius had a second transformer—indeed, he had no reason to think otherwise.

They sat awhile in silence; one could see the wheels turning in Balerion’s head. Assuming an air of indifference, he began to question the foreigner as to the location of his ship, the name of the captain, and so forth. Klapaucius answered, banking on the King’s cupidity, nor was he mistaken, for suddenly the King stood up, announced that he would have to verify what the foreigner had told him, and hurriedly left the room, locking the door securely behind him. Klapaucius then heard Balerion—evidently the wiser from past experience—station a guard beneath the window as he was leaving. Of course he would find nothing, there being no ship, no treasure, no self-winding maidens whatever. But that was the whole point of Klapaucius’ plan. As soon as the King was gone, he rushed over to the desk, pulled the device from the drawer and quickly placed it on his head. Then he quietly waited for the King to return. It wasn’t long before there were heavy footsteps outside, muffled curses, the grinding of teeth, a key scraping in the lock—and the Commissioner burst in, bellowing:

“Scoundrel! Where’s the ship, the treasure, the pretty puzzles?!”

But that was all he said, for Klapaucius leaped out from behind the door and charged like a mad ram, butting him square in the head. Then, before Balerion had time to get his bearings inside Klapaucius, Klapaucius, now the Commissioner, roared for the guards to throw him in jail at once and keep a close eye on him! Stunned by this sudden reversal, Balerion didn’t realize at first how shamefully he had been deceived; but when it finally dawned on him that he had been dealing with the crafty constructor all along, and there had never been any wealthy foreigner, Balerion filled his dark dungeon with terrible oaths and threats—harmless, however, without the device. Klapaucius, on the other hand, though he had temporarily lost the body to which he was accustomed, had succeeded in gaining possession of the personality transformer. He put on his best uniform and marched straight to the royal palace.

The King was still asleep, they told him, but Klapaucius, in his capacity as Police Commissioner, said it was imperative he see His Highness, if only for a few moments, said that this was a matter of the utmost gravity, a crisis, the nation hanging in the balance, and more of the same, until the frightened courtiers led him to the royal bedchamber. Well-acquainted with his friend’s habits and peculiarities, Klapaucius touched the heel of Trurl’s foot; Trurl jumped up, instantly wide-awake, for he was exceedingly ticklish. He rubbed his eyes and stared in amazement at this hulking giant of a policeman before him, but the giant leaned over and whispered: “It’s me, Klapaucius. I had to occupy the Commissioner—without a badge, they’d never have let me in—and I got the device, it’s right here in my pocket…”

Trurl, overjoyed when Klapaucius told him of his stratagem, rose from the royal bed, declaring to all that he was fully recovered, and later, draped in purple and holding the royal orb and scepter, sat upon his throne and issued several orders. First, he had them bring from the hospital his own body with the leg Balerion sprained on the harbor steps. This swiftly done, he enjoined the royal physicians to tend the patient with all the skill and solicitude at their disposal. Then, after a brief conference with his Commissioner, namely Klapaucius, Trurl proclaimed he would restore order in the realm and bring things back to normal.

Which wasn’t easy, there being no end of complications to straighten out. Though the constructors had no intention of returning all the displaced souls to their former bodies; their main concern, actually, was that Trurl be Trurl as soon as possible, and Klapaucius Klapaucius. In the flesh, that is. Trurl therefore commanded that the prisoner (Balerion in his colleague’s body) be dragged from jail and hauled before His August Presence. The first transfer promptly carried out, Klapaucius was himself again, and the King (now in the body of the ex-commissioner of police) had to stand and listen to a most unpleasant lecture, after which he was placed in the castle dungeon, the official word being that he had fallen into disfavor due to incompetence in the solving of a certain rebus. Next morning Trurl’s body was in good enough health to be repossessed. Only one problem remained: it wasn’t right, somehow, to leave without having properly settled the question of succession to the throne. To release Balerion from his constabulary corpus and seat him once more at the helm of the State was quite unthinkable. So this is what they did: under a great oath of secrecy the friends told the honest sailor in Trurl’s body everything, and seeing how much good sense resided in that simple soul, they judged him worthy to reign; after the transfer, then, Trurl became himself and the sailor King. Before this, however, Klapaucius ordered a large cuckoo clock brought to the palace, one he had seen in a nearby shop when roaming the city streets, and the mind of King Balerion was conveyed to the cuckoo’s works, while it, in turn, occupied the person of the policeman. Thus was justice done, for the King was obliged to work diligently day and night thereafter, announcing the hours with a dutiful cuckoo-cuckoo, to which he was compelled at the appropriate moments by the sharp little teeth of the clock’s gears, and with which he would expiate, hanging on the wall of the main hall for the remainder of his days, his thoughtless games, not to mention having endangered the life and limb of two famous constructors by so frequently changing his mind. As for the Commissioner, he returned to his duties and functioned flawlessly, proving that a cuckoo mentality was quite sufficient for that post. The friends finally took their leave of the crowned sailor, gathered up their belongings, shook the dust of that troublesome kingdom from their feet, and continued on their way. One might only add that Trurl’s final action in the King’s body had been to visit the Royal Vault and take possession of the Royal Diadem of the Cymberanide Dynasty, which prize he had fairly earned, having discovered the very best hiding place in all the world.

The Fifth Sally (A)

or

Trurl’s Prescription

The Fifth Sally (A)

or

Trurl’s Prescription

Not far from here, by a white sun, behind a green star, lived the Steelypips, illustrious, industrious, and they hadn’t a care: no spats in their vats, no rules, no schools, no gloom, no evil influence of the moon, no trouble from matter or antimatter—for they had a machine, a dream of a machine, with springs and gears and perfect in every respect. And they lived with it, and on it, and under it, and inside it, for it was all they had—first they saved up all their atoms, then they put them all together, and if one didn’t fit, why they chipped at it a bit, and everything was just fine. Each and every Steelypip had its own little socket and its own little plug, and each was completely on its own. Though they didn’t own the machine, neither did the machine own them, everybody just pitched in. Some were mechanics, other mechanicians, still others mechanists: but all were mechanically minded. They had plenty to do, like if night had to be made, or day, or an eclipse of the sun—but that not too often, or they’d grow tired of it. One day there flew up to the white sun behind the green star a comet in a bonnet, namely a female, mean as nails and atomic from her head to her four long tails, awful to look at, all blue from hydrogen cyanide and, sure enough, reeking of bitter almonds. She flew up and said, “First, I’ll burn you to the ground, and that’s just for starters.”

The Steelypips watched—the fire in her eye smoked up half the sky, she drew on her neutrons, mesons like caissons, pi- and mu- and neutrinos too—"Fee-fi-fo-fum plu-to-ni-um.” And they reply: “One moment, please, we are the Steelypips, we have no fear, no spats in our vats, no rules, no schools, no gloom, no evil influence of the moon, for we have a machine, a dream of a machine, with springs and gears and perfect in every respect, so go away, lady comet, or you’ll be sorry.”

But she already filled up the sky, burning, scorching, roaring, hissing, until their moon shriveled up, singed from horn to horn, and even if it had been a little cracked, old, and on the small side to begin with, still that was a shame. So wasting no more words, they took their strongest fields, tied them around each horn with a good knot, then threw the switch: try that on for size, you old witch. It thundered, it quaked, it groaned, the sky cleared up in a flash, and all that remained of the comet was a bit of ash—and peace reigned once more.

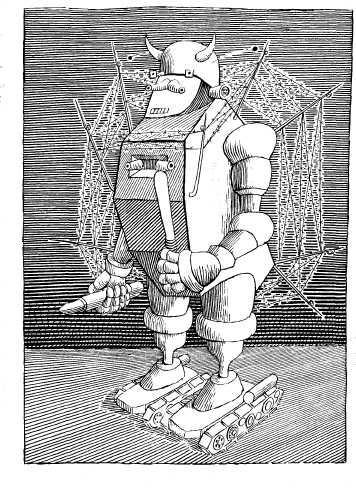

After an undetermined amount of time something appears, what it is nobody knows, except that it’s hideous and no matter from which angle you look at it, it’s even more hideous. Whatever it is flies up, lands on the highest peak, so heavy you can’t imagine, makes itself comfortable and doesn’t budge. But it’s an awful nuisance, all the same.